States of Walking, Having the Audacity, and Tacky Spectacles

A brief investigation into why buildings lie, aircraft seats don’t, and the past never happened.

Greetings from the air.

I'm currently on a red-eye from SFO to D.C., already regretting the decision. I am coming back from a 6 days trip to my former home of six years, Berkeley CA. Amongst meeting loved ones, friends, and eating as much pizza as humanly possible (shout out to Che Fico & Junes), the trip coincided with the 20th anniversary of the Berkeley Center for New Media (BCNM), where I joined other alumni for a series of talks and sessions.

On Silicon Fantasy Campuses and Human Movement

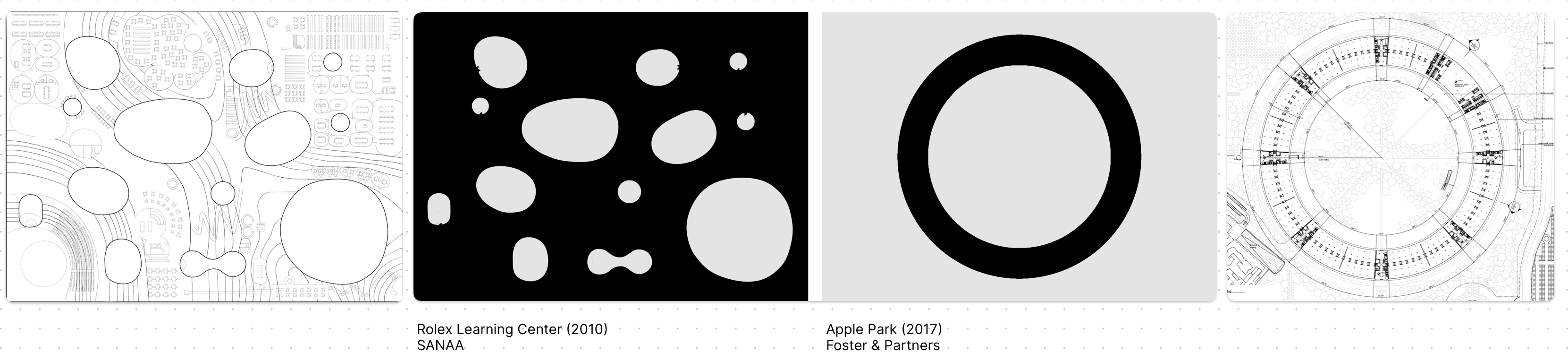

In a panel titled “Geospatial Technologies and the Organization of Urban Space,” T.F. Tierney spoke about the evolution of the Silicon Valley campus. Covering some major cases from 1960s onwards, one example stood out: the now all too famous Apple Park, designed by Foster and Partners. Specifically, what really stayed with me was that, allegedly, the shape of the floor plan resulted from a year-long study on how people move naturally in their environments. That movement study led to a hallway shaped like a perfect circle.

That claim brought to mind Kazuyo Sejima and Ryue Nishizawa’s approach to the Rolex Learning Center. In a documentary I saw years ago (one I now can’t locate unfortunately but here’s the closest thing I could find) they described how humans don’t move in straight lines, like trains. Movement, they suggested, is not linear but curved, drifting, soft. That sentence stayed with me long enough to end up on a post-it above my desk throughout undergrad. Rewatching footage now, I can’t help but think: these two buildings don’t just look unrelated, they look like exact opposites.

So here’s what I can’t stop thinking about while squeezed into a tiny economy seat so that I don’t think of the turbulence: my seat is very honest about what it is. It is the product of an unapologetic sequence of optimizations. From quarter revenue optimization for United to flight-weight optimization for the aircraft itself, this seat is uncomfortable but will not lie about it. Who would ever believe that this seat that single-handedly triggers my claustrophobia is designed for “human comfort”?

Honestly, I am not a hater: the Apple Park is a lot of really amazing things. It runs on 100% renewable energy, its design is certainly ambitious, and it hosts a company that lives and breathes innovation. That’s all fine but I find it extremely hard to believe it’s designed with “humans” in mind; neither for the employees, nor for the labor that sustains the life within the building (e.g. cleaning staff).

The question emerges: how much of what we perceive of the building as “architecture” is the building per se, and how much of it is the story we craft around it afterwards? Most importantly, how much of it is purely about latent ideologies?

This idea of narrative covering for ideology came up again when Jillian (Lee) Crandall later spoke about “states that do not exist” or online communities organized around digital currencies like Praxis Nation and Liberland. These are ideological platforms looking for territory. Some go as far as commissioning architecture. For example, and to nobody’s surprise, Patrick Schumacher has submitted designs.

Moving on.

The logic is similar: abstract power seeking form. Whether it’s a trillion-dollar company retrofitting myth into its headquarters, or a crypto-backed microstate giving itself a skyline, architecture gets pulled in to legitimize something that may not hold up on its own. While definitely not in the same lines, I was reminded of Ingrid Burrington’s State of Uncertainty (who coincindentally I had the pleasure to listen to live in that same room, exactly 4 years ago).

On Research, Receipts, and That Gut Feeling

In between sessions, I decided to quickly pay a visit at an all time favorite place of my graduate years: Moe’s Books on Telegraph Avenue, where I picked up The Dawn of Everything by David Graeber and David Wengrow. I’m about 100 pages in so the future is long on this one. One of the dominant narratives Graeber and Wengrow take aim at (through the lenses of “inequality”) is the idea that the past was somehow better, more balanced, more meaningful. It’s a form of nostalgia we’ve been recycling for centuries. However, they don’t ease into it.

What has struck me so far is how unapologetic they are in questioning core assumptions. No hedging, no pretending to be neutral. It made me think about research, and how often we’re told to suppress belief or bias in the name of objectivity. But nobody spends years chasing a theory they feel neutral about. There’s always a trigger, a contradiction, a gut feeling that something doesn’t add up.

The reason why it hit home was that a few days earlier, I had given a talk in NTUA Athens that dealt with some foundational ideas in media and information theory. Specifically, simulation and speed. After a lot of back and forth, I decided to position my argument against some of the heavyweights, whose work I still admire deeply. And like clockwork, the moment you challenge the canon, the expectation is clear: come armed. Bring receipts, documentation, historical awareness, and a bibliography the size of a carry-on.

Sure, a guy 60 years ago might’ve taken shrooms and coined a sexy theory, but you’re expected to spend five years digging through all of human philosophy just to earn the right to question him. Ironically, many of these thinkers (like Lyotard, who later called The Postmodern Condition a parody and his worst book) were the first to question themselves.

The truth is, no one builds a case against dominant frameworks purely out of disinterested inquiry and love for all things objective. You start with a feeling. A contradiction. A sharp edge you keep bumping into. Sometimes it's about the theory. Sometimes it’s about your daddy issues. Either way, it’s gloriously biased and that’s what moves it forward.

Which brings me back to this idea of romanticizing the past as a generational reflex. It’s beautifully captured in Midnight in Paris—a film I mention with hesitation.* Owen Wilson’s character travels to the 1920s and is instantly enchanted. Then he meets Marion Cotillard’s character, who’s from the 1920s, and she wants to stay in the Belle Époque. And so it goes. Everyone looks back. Everyone thinks the golden age already happened. It’s a loop.

“I’m having an insight now, it’s a minor one but it explains the anxiety in the dream that I had. I run out of Zithromax and then I went to see the dentist and he didn’t have any novocaine. You see what I am saying? These people do not have any antibiotics.” - Owen Wilson in Midnight in Paris

On Billionaires Doing Tourism in the Stratosphere

There was a time when a rocket launch was the material of awe and wonder, where we would all rush to our terraces to see the night sky change momentarily to something extraordinary and magical. Fast-forward seven years, now five women—including Katy Perry and Jeff Bezos’ fiancée—were launched into the stratosphere by Blue Origin. The purpose wasn’t scientific. They went up, looked around, and came back down.

We’re officially at the part of the dystopia where space tourism is a leisure activity. Yet despite the grim levels of this realization, I got hope from how the internet responded: with collective side-eye and well-earned sarcasm. Maybe we’ve reached a turning point. Maybe the spectacle is so obvious, so tacky, that it finally breaks its own spell.

Maybe critical thinking isn’t coming back because of education or enlightenment, but because reality has gotten too absurd to tolerate without it.

That’s all for now. I’ll report back when I finish The Dawn of Everything, possibly even more certain that certainty is the real myth.

Until then, still chewing. —Ioanna

*For clarity: I don’t endorse Woody Allen in any way, and I find much of his personal history deeply disturbing. That said, I do believe it’s possible (and sometimes necessary) to extract value from a work of art without supporting the artist behind it. Referencing a scene to illustrate an idea isn’t the same as celebrating or enabling the person who made it. I bring this example up for what it reveals, not for who created it.